There’s a new “feature” in Sonoma, and no one besides Apple is quite sure what it is.

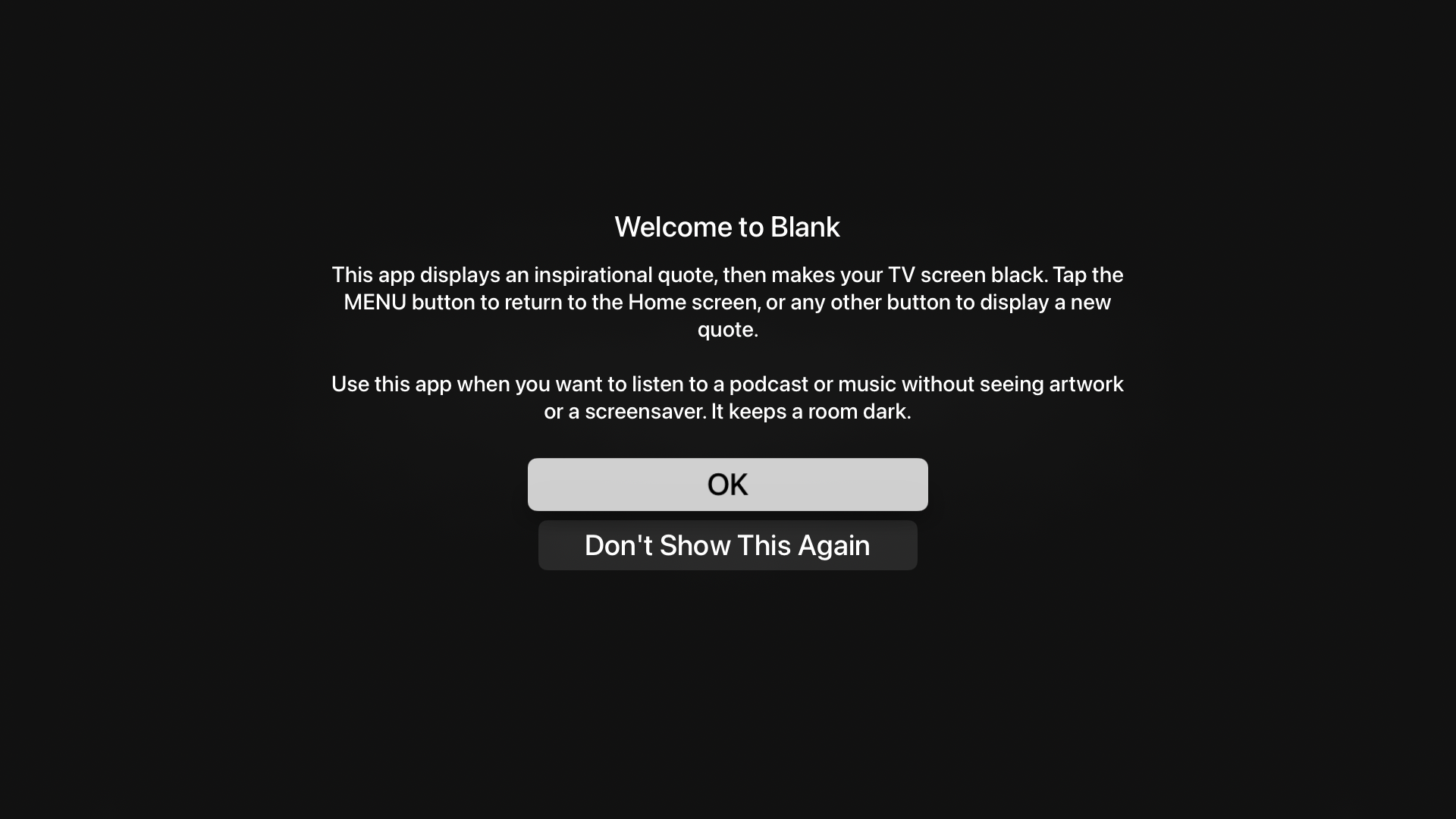

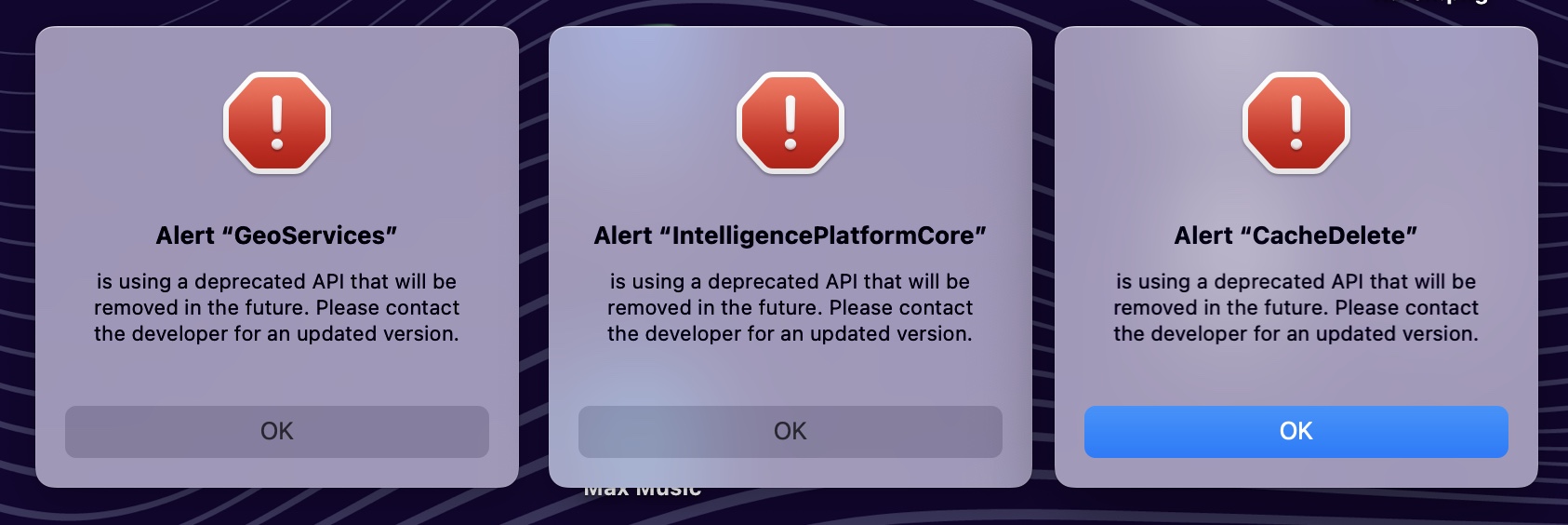

Alerts for deprecated APIs are now appearing frequently. Sometimes when you launch an app, and sometimes at random. Here are three I got the other day after waking a MacBook from sleep:

From a UI point-of-view, these alerts have serious issues:

- They are scary and not actionable.

- The only unique information is the title. The name, however, is not something I recognize.

- I know what a deprecated API is and how its removal can be a bad thing, but ordinary users won’t.

- There is no mention of what API caused the alert.

- I’m advised to contact the developer for an updated version, but there is no information on who that developer is. (In the screenshot above, I’m assuming the developer is Apple itself, so I notified them with FB12560773, FB12560774, FB12560776).

But the UI is just the beginning of the fun. Once the developer is notified, the lack of information for this “feature” prevents the deprecation from being addressed.

This alert is mentioned in the release notes for the first beta for Sonoma. The brevity of that note is surprising for such a prominent and important addition to macOS.

I suspect that the brevity of the alert’s text is to shield the customer from unfamiliar terminology and complexity. It’s like a check engine light in your car: it comes on and you know to get to a mechanic ASAP.

When you get to the mechanic, they have diagnostic tools that let them understand what’s wrong (the engine control unit will typically store a unique code).

The difference with this “feature” is that folks like me are the mechanics and we have no diagnostic code. Supposedly, this alert should only appear with the use of ATS or ATSUI (per the release notes), but I find it hard to believe that modern system framework components shown above are using Apple Type Services that were replaced 13 years ago. But maybe they are – we all embed frameworks into our apps, some where we have source code, others where we do not.

The alerts also have another hideous “feature”. They turn themselves off as soon as you hit the OK button. They never repeat, so it’s impossible to bisect the code to find and verify a fix.

It’s like having your check engine like go off the next time you start the car, and the diagnostic code being removed by the time you get to the repair shop. A developer’s reaction to these reports will be the same as your local mechanic: “I don’t know what’s wrong. Good luck.”

If Apple wants developers to repair these deprecations they need to make major changes:

- Document the behavior, including all of the APIs that trigger it.

- Tell developers if this is something that will only appear in the beta or if it will be a part of the final release.

- Give the customer something to work with when communicating with the developer. A diagnostic code at a minimum.

- Log information about what caused the issue: remember that it may not be the developer’s own code triggering the alert. Plugins, embedded libraries, and external frameworks should be a part of the log. These logs should be available to customers so they can provide them to developers.

- Give developers a way to reset the alerts. Make fixes testable.

Without these changes a Mac user’s future is one with a lot of crashes caused by deprecated code.

NOTE: This blog post has been submitted as feedback. If you find this situation intolerable, please submit a duplicate titled “Mysterious deprecation alerts in Sonoma” with a reference to FB12560999 and a link to this blog post.