The bank we use for our business account recently mandated the use of a product called Trusteer Rapport while accessing our information online. Although Mac OS X doesn’t have any problems with “increasingly sophisticated malware in the online environment”, I do need to periodically check our accounts and transactions so I proceeded with the installation.

The first warning sign was after starting the Installer: I was prompted for an administrator password indicating that this software wanted to run from protected areas of my system. Being a developer, I immediately dug into the installer scripts and configuration files to see that the app is placing items in the Rapport/bin, PreferencePanes, LaunchDaemons and LaunchAgents folders of the main system Library folder. The launch folders indicate that the software will be run whenever my Mac is restarted and will be able to do things a normal user would not (because of elevated permissions.)

I placed my security concerns aside as I need to access my bank website, so I went ahead with the installation. Afterwards, I was directed to a web page describing the new software.

Again, as a developer, my first thoughts were suspicious ones. From experience, I know that it’s not easy to modify Safari’s user interface in the way that Trusteer was doing. My guess that there would be a new, always active, background process was confirmed by the presence of “rooksd” in my process list.

However what happened next really opened my eyes. Safari crashed.

Of course that, in and of itself, isn’t the end of the world. But I was surprised to see a new library named RapportUtil1 while looking at the Safari crash report. It was pretty clear that the new Trusteer software caused the crash. But how?

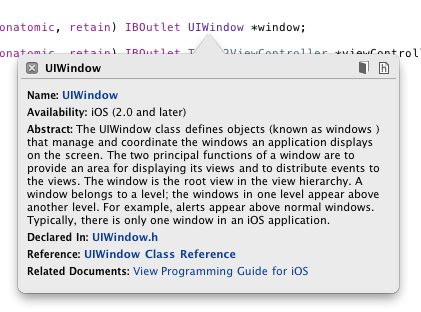

As a longtime Objective-C developer, I know a thing or two about “method swizzling“. In a nutshell, this allows a developer to replace the functionality of code they don’t have direct access to (typically in the system or other frameworks.)

Seeing “_nsapplication_sendEvent_override” tells me that Trusteer is using this technique to change the behavior of Safari. The function that is being affected is -sendEvent: — the part of every Cocoa application where mouse, keyboard and other input is routed.

Method swizzling is a dangerous activity. You have to make assumptions about how some other code, that you’ve never seen, is behaving. You also need to think about how that code might change in future versions. There are extreme cases where this technique can be effective: overriding the default behavior of my web browser is not one of them.

It’s clear that the folks taking control of my browser aren’t as clever as they think. Do you see a common theme when you search Apple’s discussion forums for “RapportUtil1“?

Even more troubling is the method being overridden: every key press or mouse movement is first being sent to Rapport and then forwarded onto Safari. Since this happens often, the intruding software can do pretty much whatever it wants, whenever it wants. And remember that part of this package is running with elevated permissions in the background.

After mentioning my findings on Twitter, I got back some very interesting replies. Graham Lee (@iamleeg) pointed out that I’m not the first developer to question the technical merits of this software. But then Peter Hosey (@boredzo) dropped the real bomb. Trusteer tacitly admits to recording my password. That’s easy to do when you take control of -sendEvent:.

Essentially, my bank is asking me to install is a keylogger. Just so they can warn me not to use the same password on suntrust.com and playboy.com.

Hopefully, the engineers behind Rapport are smart enough to be using hashed passwords rather than clear text. And hopefully none of the personal information Safari has access to is being forwarded to the Trusteer servers. And hopefully they’re not recording how many times I visited playboy.com last month. But that’s beside the point, because as a closed source product, no one can audit their activity. That’s not true with Safari.

Oh, and there’s one other thing: the Rapport software isn’t supported on Lion. One of the tenets of method swizzling is to test your software early and often with any new release of the system or framework that it’s modifying. As a developer, you need to be proactive about fixing any problems that pop up in the code you are overriding. Not doing so is irresponsible and puts your users at risk. The last update for Rapport was in 2009.

(One could speculate that the new privilege separation architecture for Safari in Lion is causing Trusteer’s developers a lot of headaches. The other tenet of method swizzling is to remember that it’s not a matter of if your hack will break in the future, but rather when it will break and how painful it will be to fix.)

Needless to say, I have uninstalled this software and will never be installing it again. I would recommend this course of action to any end user.

But that leaves me with a problem: how do I access my bank’s website? I have three options:

1) Find another bank. This is a difficult choice, as there are many systems that are hooked up to this account: ACH transactions for sales via iTunes, bi-weekly payroll, automatic payments for services, etc. I’d also like to give SunTrust a chance to reconsider their position in requiring this software (they will be getting a copy of this report.)

2) Use the telephone. I can call the bank when I need the information. Sure they’ll get tired of hearing from me, and it will cost them more for customer service, but it’s their choice to require Trusteer Rapport.

3) Run the Trusteer Rapport software in locked down environment. Once it’s supported on Lion, it should be possible to create a virtual machine that that will only be used to access the bank website. Needless to say this is inconvenient, a waste of resources, and severely limits my ability take advantage of my bank’s services.

In closing, I’ll leave you with one final irony: I will never be able to access my bank’s website from what is arguably the most secure computing device in existence today. That’s because the iPad is not a supported platform. Apple only allows third-party applications to run in a secure sandbox where they can’t affect other applications or the operating system. What you’ve seen above is exactly the reason they’ve done this.