In my last post about AppViz, I mentioned that I spent about six months creating an internal accounting tool called BeanCounter. Why the hell did I do that?

Because I don’t want to run my business on financial guesses based on iTunes Connect sales reports.

The Need For Financial Accuracy

For many app developers and iBook publishers, income from iTunes Connect is a significant part of the business’ financial statement. In many cases, the App Store is a developer’s only distribution channel, so it’s responsible for 100% of gross revenue.

When you have a financial statement, you want it to be exact. If your local tax collector comes calling and you show them guestimates, you’re in for a rude awakening. You’ve got a paper trail that’s fishy and that’s going to invite closer scrutiny. It’s the reason every piece of accounting software ever written has a reconciliation feature.

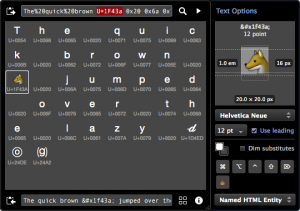

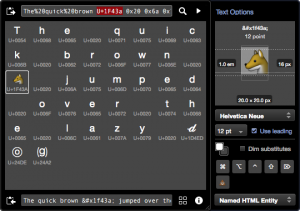

Publishers pay author royalties and many app developers split revenue with a designer. When it comes time to share the monthly Apple ACH deposit, financial guesses are also a problem. Not only will you be giving your partners the wrong amount of money, you’ll eventually be reporting it incorrectly on a 1099-MISC. Your estimated payments can be off by thousands of dollars:

Sales Reports Are Not Accurate

The root of the problem is that all services except AppViz 3 use fluctuating values like fiscal calendar ending dates, payment clearing dates, and currency exchange rates. If you do, you’re making financial guesses.

Don’t take my word for it, here’s what App Annie has to say:

Why do my sales reports in App Annie not exactly match my financial reports in iTunes Connect?

App Annie fetches the sales data from the iTunes Connect “Sales and Trends” section. There are a few reasons why the sales data doesn’t match Apple’s “Financial Reports” and the amount of money you receive from Apple.

Fiscal calendar. Apple uses fiscal months rather than calendar months for payouts. To see Apple’s fiscal calendar, go to “Payments and Financial Reports” and click the “Fiscal Calendar” link. For example, fiscal March 2011 starts on Feb. 27 and ends on Mar. 26.

Clearing of payments. What matters in the case of financial reports is what payments were made during a fiscal month, not how many downloads were made. Since most people use credit cards to buy apps, it can take up to 2-3 days for a payment to go through. Also, some payments never go through!

Currency conversions. Apple’s “Financial Reports” use Apple’s own currency rates, whereas App Annie always uses today’s exchange rate.

Remember that the last two points above have a certain degree of unpredictability, which makes the figures we get from Apple’s “Sales and Trends” slightly different from the figures in Apple’s “Financial Reports”.

That last item is particularly bad: currency fluctuations will give you wildly inaccurate accounting. For example, let’s say you sold €10,000 of product and used the rate on October 28th, 2013 (1.38) to convert that amount to $13,800. Then, Apple deposited $13,400 into your account on November 7th using that day’s 1.34 rate. Hope you didn’t pay your partners using that financial guestimate of $13,800!

The bottom line is this: you cannot rely on estimates in Sales Reports when doing financial reconciliation or partner payouts. Only Financial Reports can be used for this purpose.

Financial Calculations Are Hard

The problem is compounded when you have multiple products with different partners. Figuring out how to divvy up the money turns out to be a hard problem and it’s why everyone else has punted on doing it right. It’s also a competitive advantage for us, so I’m not going to go into any details about how we get the numbers to come out right.

I will, however, give you a peek into the first hurdle you’ll encounter: you can’t use floating point values for financial calculations. If you write code like this, you’ll be in for a world of hurt as errors accumulate:

double subtotal = balanceTotal +

(salesTotal + adjustments);

if (subtotal != 0.0) { // is 0.00000001 a zero value?

rate = deposit / subtotal;

}

Cocoa has an awesome subclass of NSNumber called NSDecimalNumber. Classes like NSDecimalNumber are one of the reasons that “NeXTSTEP had a long history in the financial programming community.”

When using NSDecimalNumber your code will get more verbose than the snippet above. But more importantly, it will now be exact:

NSDecimalNumber *subtotal = [balanceTotal

decimalNumberByAdding:[salesTotal

decimalNumberByAdding:adjustments]];

if ([subtotal compare:[NSDecimalNumber zero]]

!= NSOrderedSame) {

rate = [deposit decimalNumberByDividingBy:subtotal];

}

It also forces you to think about problems like rounding: do you want to use NSRoundBankers when your code calls -decimalNumberByRoundingAccordingToBehavior:?

Conclusion

I hope you now see why I thought it was wise to spend a lot of time coming up with a system that ensures financial accuracy. I’m also thrilled that this system is now a part of AppViz 3, the app that’s been keeping track of our products on iTunes Connect since the App Store first opened in June 2008.

It also makes me happy that other developers are seeing the same benefits for accurate financial reconciliation. Helping other developers is what makes me tick.

Take a moment to think about how these issues affect your own business and then take a look at AppViz 3. I think your balance sheet, your partners and the tax man will be happy you did.