Last week’s 40th anniversary of the Mac got me thinking. I’ve also been contemplating this week’s release of Apple Vision Pro.

It feels like we’re at a crossroads for platforms, but one that’s impossible to pass.

I was one of the folks who bought a Mac in 1984. At the time I was a member of a team building a Unix workstation from the ground up. We had bigger displays, better networking, faster processors, more memory, and larger disks.

But we were all jealous of what the team at Apple had done. That first Mac and its system software was brimming with new user interface ideas and techniques. Better ways of doing everything we had done.

And you can say the same thing about Apple Vision Pro and visionOS.

Except there is a problem.

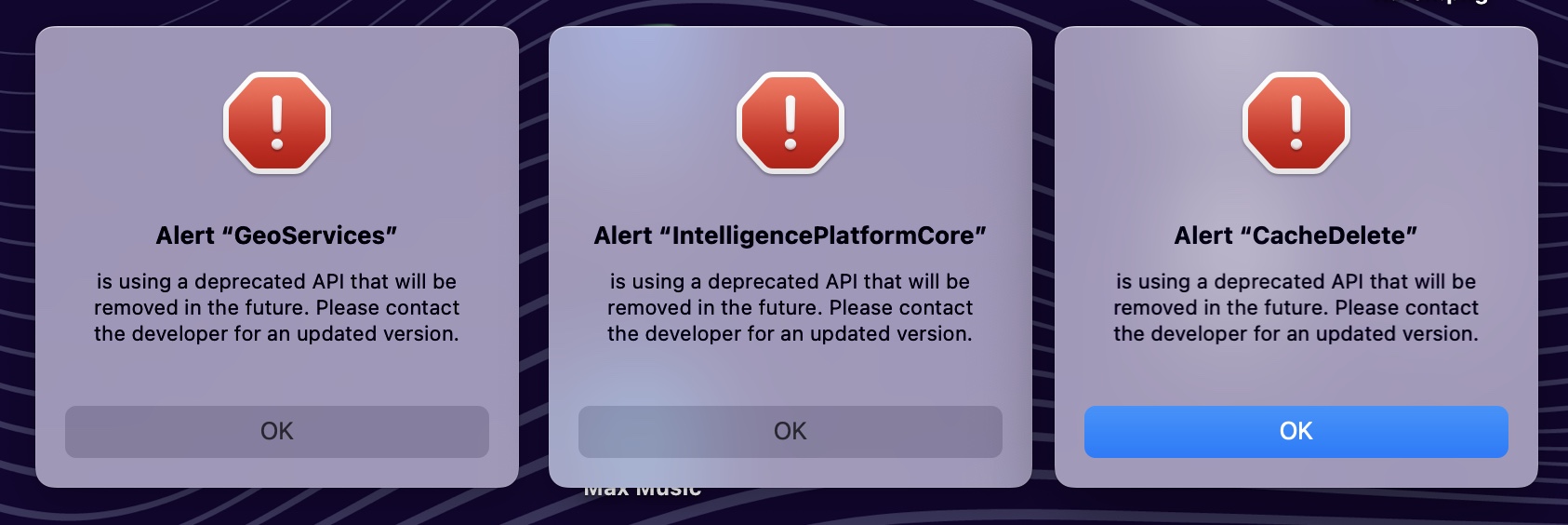

Processes

If you’re a software developer, the Apple Vision Pro cannot be used standalone for your work. You’ll be able to use it as much as you do an iPad. You can experiment in Playgrounds and build some simple apps, but you’ll quickly hit a wall.

That’s because developers use a lot of processes. And these processes talk to each other in very creative ways. Maybe it’s as simple as creating child processes to handle work. Maybe it’s a more complicated process like a Docker container running a web server that talks to a database process via a Ruby on Rails process. There are processes everywhere you look.

And in an Apple sandbox, you get one process. You can’t fork and exec a child. And if you query the Mach kernel for information about another process, you get back KERN_FAILURE.

(To get a very good idea of what’s possible at the fringes of a sandbox, take a look at a-Shell on your mobile device. It does an amazing number of things, but you’ll quickly feel frustrated that ps, kill, top, and anything else that deals with processes is missing.)

There is a good reason for apps only having visibility of their own state. Imagine the kind of fingerprinting that Google and Facebook could do by seeing what apps you’re using. We’ve already seen apps trying to do the same thing using URL schemes.

When my pal John Gruber talks about Macs doing the heavy lifting, it’s not just about complex and resource-intensive tasks. It’s also about the security exposure: the Mac is the only “dangerous” Apple platform.

Windows

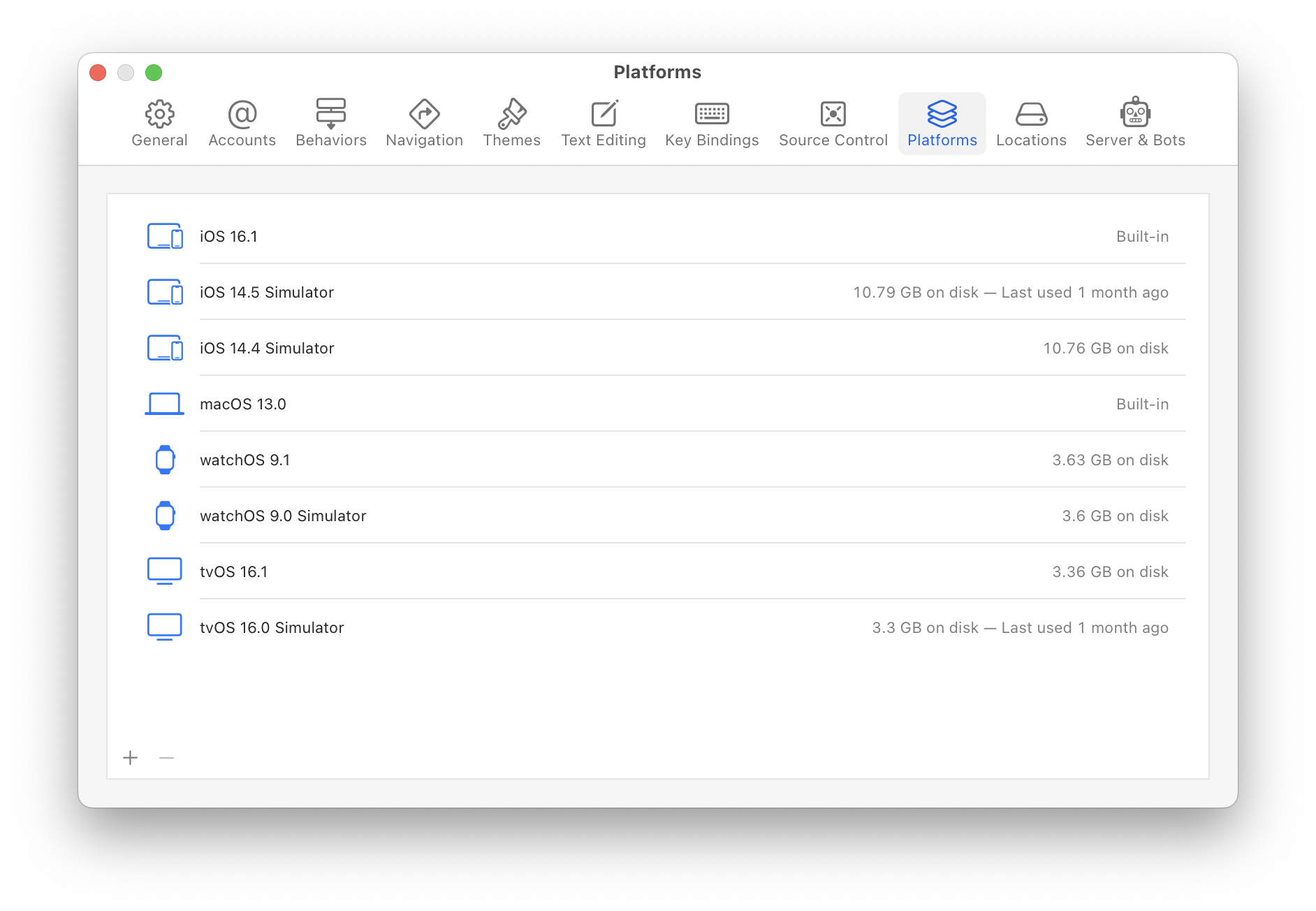

There is a thing that developers love almost much as processes: windows. We have so damn many. Hundreds on a good day. Thousands on a really good day.

And this is why I get frustrated every time I see a demo of Apple’s headset. I can easily imagine fitting my work into a space with an infinitely large interaction surface.

As it is now, you get to see a screen or two streamed from your Mac. That will surely improve; probably to the point where you have individual windows in your spatial environment.

But you’ll still be carrying the Mac around to get any work done. Somewhat ironically, the Apple Vision Pro is not doing the heavy lifting, but it will be the thing that’s cumbersome in your daily life.

Here’s a comparison of the headset’s carrying case and a MacBook Air:

The Apple Vision Pro is almost 15 times taller than the MacBook Air. Even worse, I can’t even close my backpack, much less fit in a laptop:

After the Mac was introduced, you didn’t have to carry around an Apple ][ or Lisa to do software development.

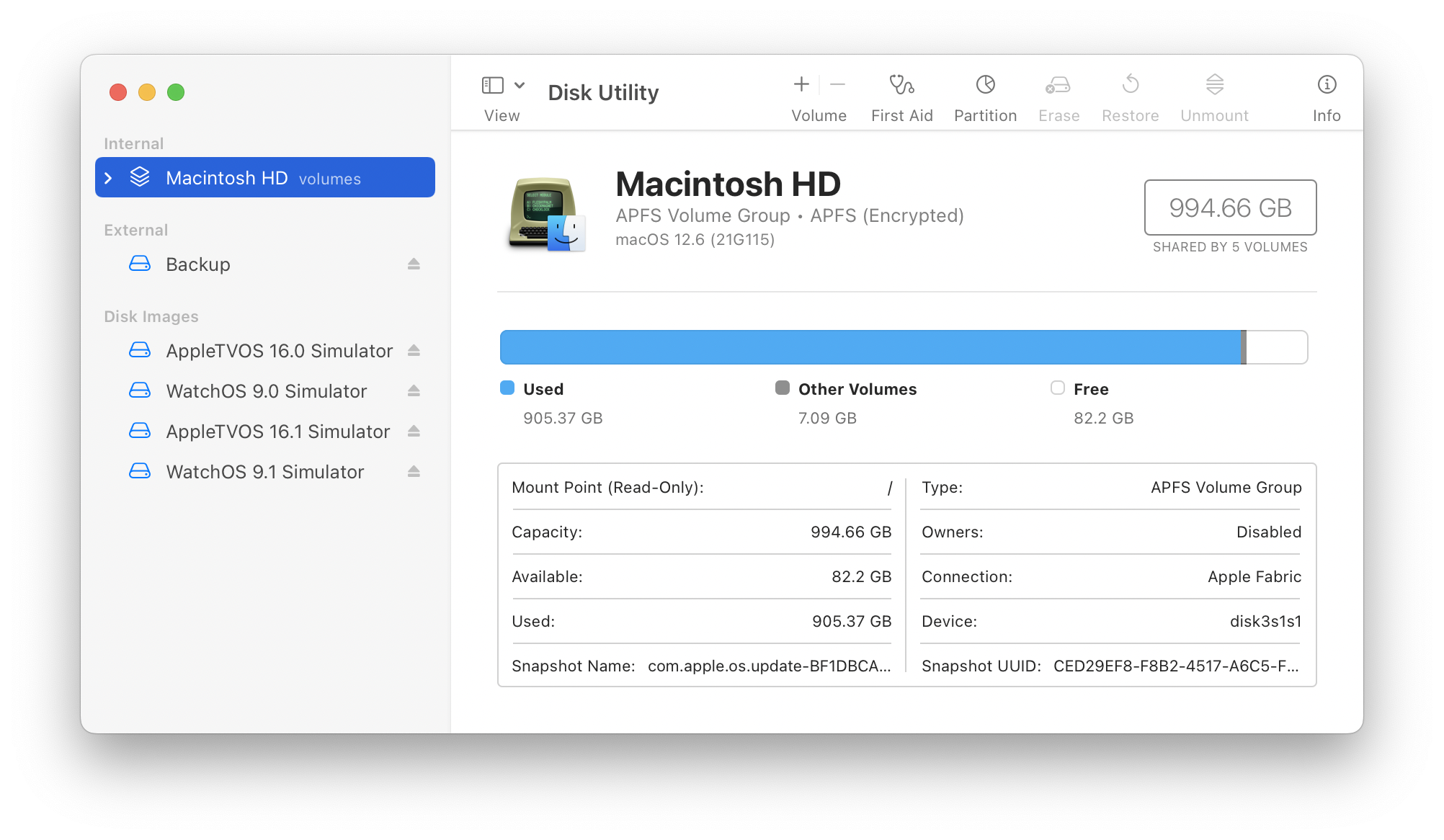

Yet here we are because the Apple Vision Pro is locked down. It’s being relegated to being a fancy display for software developers. That’s not necessarily a bad thing and there’s no extra cost for a display stand.

But…

This isn’t a sustainable situation for the next 40 years. Without some low-level structural changes in visionOS, it will never thrive as a developer platform. Just as the iPad has not.

It also doesn’t bode well for the Mac. I’m sure Apple can continue to add incremental changes to satisfy developers, but there won’t be anything revolutionary with how we work. There is also little incentive for Apple to change here: you are buying an Apple Vision Pro along with a MacBook, after all.

One of the extrordinary things that happened back in 1984 was the ability to have more than one terminal window. Even though my Mac had to be connected to a VAX 11/780 over a serial cable (sound familiar?), this was a completely new way of working. We were suddenly free of working within the confines of a single 24×80 character display.

Once we broke free of those limitations, things like visual development environments took hold. I’m pretty sure Apple understands the productivity benefits that came along with these changes.

And here’s the thing: developers don’t come up with these ideas unless they have a place to experiment. Seeing multiple windows that contained code, debugging, and other tools led some folks to start thinking about integrating this environment using the new interaction mechanisms.

Those same kind of folks may find inspiration in spatial computing, but will ultimately get thwarted by the restrictions of a single process. An architecture developed for mobile devices with only one app on the screen is now being used for apps on an infinitely large screen.

Apple Vision Pro is a technical marvel, but ultimately falls short in ways that satisfy the natural curiosity of developers.

That’s a shame. I just hope some smart folks at Apple feel the same frustration I do, because we need a future beyond the Mac.