Tim Cook has openly stated that Apple is working on “new product” categories. Many people, customers and competitors alike, assume that means some kind of wearable computing device. And of course that means it has to be some kind of “smartwatch”, right?

I don’t think so.

The Market

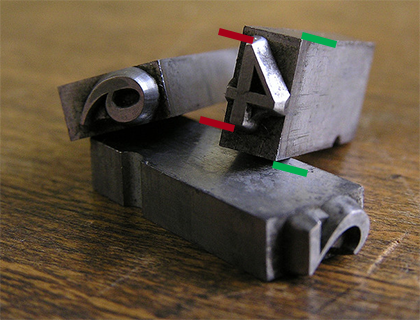

First, let’s look at the market for quality timepieces; ones that you’d be proud to wear on your wrist. It’s dominated by companies with centuries of experience. It’s also a high-end market: spending a few thousand dollars on a nice watch is chump change. You’re buying a work of art.

Apple certainly has great designers, but they’re going to be competing against craftsmen who’ve been refining their craft since the 15th century.

I realize that this sounds a lot like Ed Colligan talking about mobile phones:

“PC guys are not going to just figure this out. They’re not going to just walk in.”

There’s a big difference here: the companies that dominated the music player and mobile phone markets were making complete crap prior to Apple’s arrival. Granted, there are a lot of cheap and crappy watches on the market, but they’re not remotely interesting to the demographic that buys Apple products. And to many people, a fine timepiece is more about status than technology.

Taking all of this into consideration, watches don’t sound like product category that fits Apple well. One of the many reasons we love their products is because they are best of breed.

The Watch

Now, let’s look at the state of the “smartwatch” market. Smart companies, like Nike and FitBit, are creating products that aren’t really a “watch”. It’s like the “phone” being the least interesting thing on our “smartphone”.

In fact, Tim Cook is already wearing one of these devices:

Walt: Is wearables a thing — is it part of the post-PC era wearables that go beyond fitness devices?

Tim: Yes, I think so. I wear a Fuelband, I think Nike did a great job.

Note: This quote, and others in this piece, were made during Tim Cook’s interview at D11.

However, once manufacturers try to put a lot of smarts in a watch, they end up with a product that’s a bulky mess or ugly as sin. Probably both.

Again, Tim Cook has noticed this same thing:

“There are lots of gadgets in the space. I would say that the ones that are doing more than one thing, there’s nothing great out there that I’ve seen. Nothing that’s going to convince a kid that’s never worn glasses or a band or a watch or whatever to wear one. At least I haven’t seen it. So there’s lots of things to solve in this space.”

We all know that Apple’s designers and developers can solve these problems. But can they do it without making compromises?

“It’s an area that’s ripe for exploration, it’s ripe for us to get excited about. Lots of companies will play in this space.”

That exploration is all about saying no a thousand times. It’s easy to create a great looking concept, but turning that fantasy into a product is where it gets hard and compromises are often made.

It’s my view that the technology needed to make that great product that does everything just isn’t there yet. There are too many compromises.

The New Hub

Let’s assume for a second that you can make a compelling device for a wrist. I’d still be asking myself this question: “Why do I need a computer on my wrist?” I already have one in my pocket.

With the introduction of CarPlay, Apple’s answer to this question is becoming clearer. That device in your pocket is the new hub for your digital data. Ben Thompson calls it Digital Hub 2.0.

You don’t need a computer on your wrist. Apple’s wearable devices will become a part of this circle that surrounds your main device. And as with CarPlay, it’s going to be a two-way street where interactions and information in the player make their way back to the main device.

The Fashion

The development of wearable technology is going to enter a space where most companies in the Silicon Valley have no experience. As a geek, do you know who Anna Wintour is and why she would be important to the success of a wearable device?

Angela Arhendts certainly does…

Put aside your geek sensibilities for a second and think about this device as a piece of fashion instead of a cool gadget. What’s the primary function of fashion?

It’s about expressing a personal style. It’s an extension of your personality and way to show it in a public way.

Look at the huge variety of iPhone cases that are on the market. That’s only 16 examples of 4.7 million search results. Fashion is as diverse as the people who wear it.

An important part of this diversity is customer’s gender: men have different tastes than women. That concept watch mentioned above looks fantastic—if you’re a male. I can’t imagine my wife wearing it.

Then there’s the question of size: as someone who’s 6’7″ tall, I know firsthand that “one size fits all” is the greatest lie ever told by clothing manufacturers. Since everyone’s body is unique, wearable devices must also consider comfort and fit in the design.

Apple may be able to use something like an iPhone case to make a wearable device appeal to both sexes. Or adjustments that make a single device (SKU) adapt to multiple body shapes. But I suspect that it’s going to take more than that to be appealing as a piece of fashion.

The Customer

Now that we’ve looked at the challenges in developing these devices, let’s think about the most important question Apple is asking itself:

Who is going to buy this wearable technology?

Trends are always set by the younger generation. Especially with clothing, jewelry and other items that appeal to a demographic with a lot of expendable income. To me, this quote by Tim Cook is the most telling:

“To convince people they have to wear something, it has to be incredible. If we asked a room of 20-year olds to stand up if they’re wearing a watch, I don’t think anyone would stand up.”

This response to Kara Swisher’s question about Apple’s interests in wearable technology covers all the bases. It includes the target market (“20-year-olds”), product focus (“has to be incredible”), and most importantly, he’s seeing the same thing I am: people don’t need to wear watches because they already have that computer in their pocket.

Note also that in the response he doesn’t say “wear a watch”, it’s “wear something”. It’s implied, but not stated. Remember that he learned from the master of misdirection: Steve Jobs.

The Product

Given everything presented above, it’s pretty clear to me that a “smartwatch” isn’t in Apple’s immediate future. But they’re clearly interested in wearable technology. So what are the alternatives for a product that could be released this year?

The first step is to start looking at things from Apple’s point-of-view. I ask myself, “What problems can a wearable device solve?”

As I think about answers to that question, it leads me to the conclusion that Jony Ive and crew aren’t looking solely at the wrist. Wearable technology could take cues from other kinds of jewelry: rings and necklaces, for example.

What if Apple’s entry into this space is a ring?

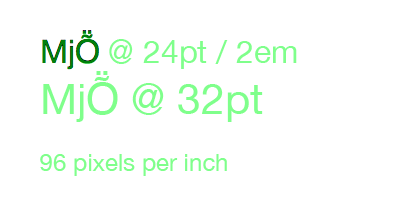

- Limited display — A discreet way to provide notifications—just an LED or two that indicate what’s happening on your iPhone. Maybe even a small, flexible E Ink display for high contrast text.

- Tactile — A way for your finger to sense a notification. It’s easy to miss audio cues in a noisy room or a vibration in your pocket.

- Small & light — A hallmark of Apple design. Simplicity in form and function.

- Customer appeal — Those 20-year-olds don’t wear watches, but jewelry is already a part of their culture. “Bling” came from the world of hip hop.

- Sensors — Your finger has a pulse and blood pressure for Healthbook.

- Power — The Lightning connector is small for a reason.

- Competition — While all its competitors are rushing watches to market, Apple catches them with their pants down.

- Low cost — How many of these rings could Apple sell if they were priced at $99?

But the biggest feature of all would be that this wearable device could support iBeacon. This technology is based on Bluetooth LE which Apple describes as “a new class of low-powered, low-cost transmitters that can notify nearby iOS 7 devices of their presence.”

Let this sink in for a second: your wearable device is transmitting a signal with a unique identifier that can be picked up by an iOS 7 device. And the proximity detection is sensitive within a few inches. Presumably, this signal could be also be detected on your Mac as well, since they have supported Bluetooth 4.0 since mid-2011.

By wearing this ring on your finger, your devices can know how close you are to them.

This opens up a world of possibilities: imagine the joy we’d all feel when a notification only popped up on the device we’re closest to. Right now my ring finger is hovering over my MacBook Air’s keyboard by 2-3 inches, while the phone in my pocket is over a foot away. Notification Center needs this information.

Conclusion

Predicting Apple’s future is always fraught with difficulties. I may not be right about the end result being something other than a watch, but I’m certain that there are people at Apple thinking about the issues I’ve outlined above.

And I, like many others, am really looking forward to wearing Apple.