January started as normal as can be expected when malicious grifters start making basic decency a radical idea. It turns out the anxiety associated with these political events would be the least of my problems throughout the year.

It felt great to finish up a 12 month project and release the first version of Tapestry. I celebrated with a trip to Louisiana visiting my wife’s birthplace, exploring islands and bayous, and eating more seafood than I thought possible.

In April, I turned 65 and signed up for Medicare. I was about to learn how important this was.

Towards the end of that month, I started feeling some tingling in my left index finger and some pain in my neck, especially after working at the computer all day. Initially, I chalked it up to the normal aches and pains of growing older, but the pain just wouldn’t go away.

The next month was marked by tragedy. On May 17th, while taking our dogs for a walk before dinner, our girl Jolie was attacked by dogs that had escaped from their yard. It took every ounce of my strength to get two 50 pound dogs without collars off of our 15 pound pup, but I rescued her, did some quick triage for her open wounds, and rushed her to the vet for four hours of surgery. We were both wrecks, but made it to see another day.

Jolie started to recover from her injuries, but she was a 15 year old with a weak heart. On June 4th, I found her unconscious outside the door of my office. She died peacefully and the loss was added to the year’s pain tally.

I also had adverse effects from the dog fight: the pain in my neck had gotten much worse. The adrenaline rush made me move my neck and arm in ways that turned an irritating pain into a persistent one.

In July, we travelled to San Diego to see an outdoor concert. I was living with neck pain all day, every day, and when I couldn’t lift my head to watch the show, I knew I needed help. On the 16th, I had my first appointment with a local chiropractor. X-rays showed degenerative spine disease, which is consistent for someone my age: pain being caused by old cervical vertebrae and pinched discs.

I was staying active in spite of the pain in my arm and neck. My swimming stroke sucked thanks to my limited arm movement and neck pain limited the length of my bike rides.

On August 3rd, while riding my e-bike to Trader Joe’s to do some grocery shopping, I was hit by a car. Someone blocking the road at a 90 degree angle decided to backup while only looking at the camera on their dashboard. They didn’t see me riding in the rightmost lane of traffic.

I ended hitting the D pillar of a SUV with my left shoulder and tearing my AC joint. Then I was thrown from my bike and landed hard on asphalt. The impact broke five ribs and I immediately had a new source of pain on my left side.

The paramedics arrived and got me to the closest emergency room. That’s when we all discovered I had another problem: a punctured lung that was causing my chest cavity to fill with air. This presented itself while lying down waiting for a CT: it’s impossible to express the panic of not being able to breathe or talk. Luckily, my wife was in the room and screamed for help that resulted in a temporary chest vent while I was rushed to a trauma center. Another ride with the paramedics, this time with lights, sirens, and lot more speed.

There was a team waiting for me, and I got a dose of ketamine, followed by a chest tube that was inserted while I was (barely) conscious. As the surgery was ending, the head nurse asked me how I was feeling, and my response was “I’M TRIPPING BALLS”, which got a laugh from everyone in the operating room. It also helped me understand a billionaire that needs the substance to feel joy in his life.

I spent a total of three days in the hospital as the doctors monitored my chest fluids. My main source of pain at that point was the broken ribs: sneezing, coughing, or laughing hurt like hell. What didn’t hurt was my neck and arm: as one nurse joked when I was telling them about my situation: “Hey, you got a free adjustment!”

I felt good enough to spend some time working on Tot 2: all of the App Store purchasing code was done while in a hospital bed. It was a nice distraction and helped us ship the update at the end of August.

Soon after the release I read a blog post that rang true: Irrational Dedication. Both of the Iconfactory’s major releases during the year were willed into existence. Tapestry after a year of work for a new product category (“timeline apps”) that was difficult to explain. Tot while working through various stages of pain.

It took about six weeks for my ribs to heal completely. While that was happening, September presented another health issue to deal with: this time for our boy dog, Pico. What started as a small bump on his butt quickly grew into a large Mastocytoma (Mast Cell Tumor). At the end of August he had surgery to remove the mass and he got a new nickname: “Zipper Butt”.

We were about to put a twist on the old adage about dogs looking like their owners: this owner was about to look like his dog.

This was also the time where my original neck pain returned. It turns out the brain can’t handle more than one pain input at a time – the broken ribs put the nerve pain on the back burner. Chiropractic treatment was providing only temporary relief, so I tried acupuncture in October.

Then, in November, all hell broke loose. At the beginning of the month we took a car trip to Tucson for a family event. I spent most of the trip through the desert with shooting pains through my arms: agony for hours on end.

A week or so later, I started noticing problems with my ability to walk and a numbness throughout my torso. The nerve pain felt like the onset of paralysis. Shit was getting serious.

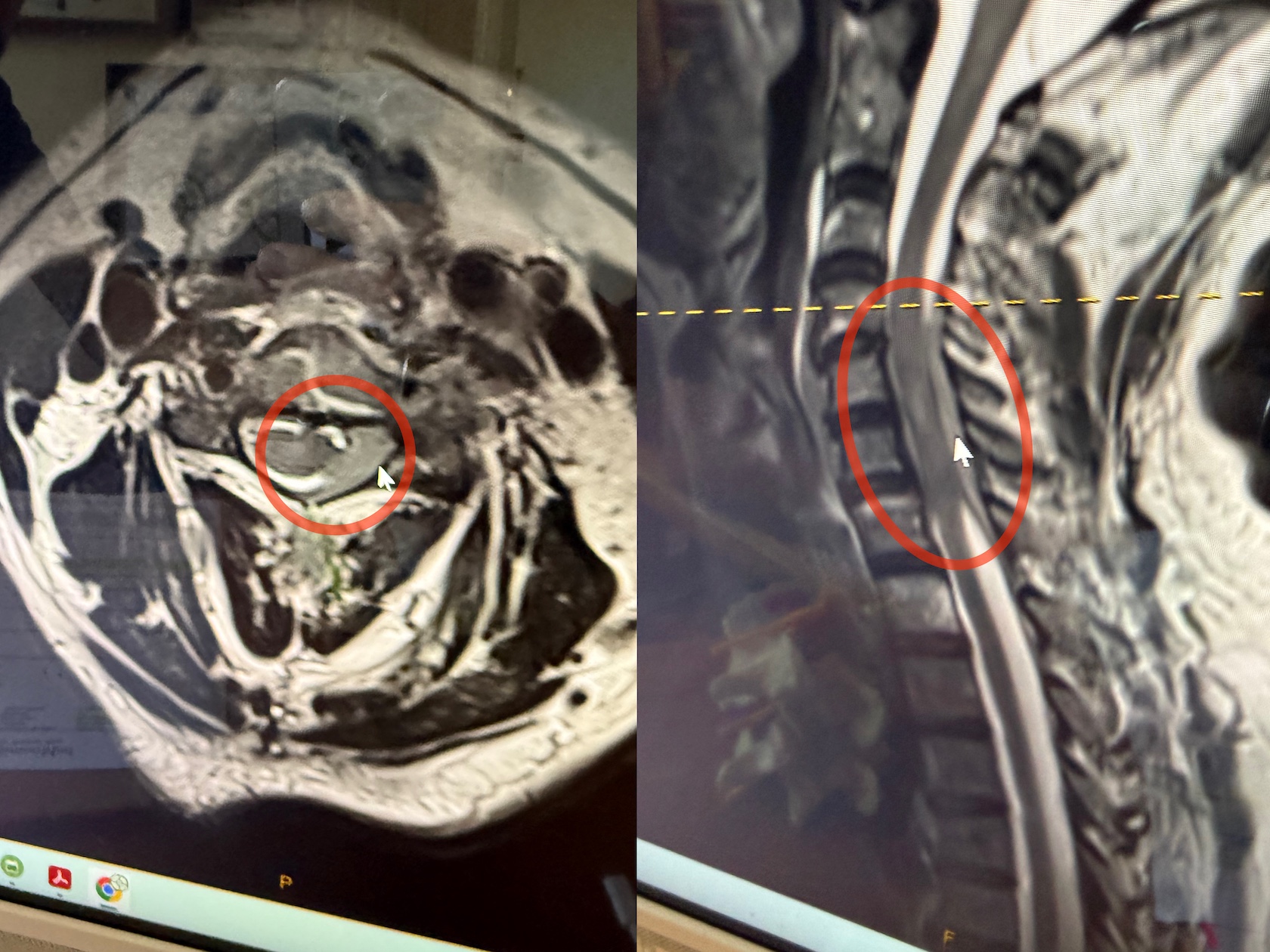

My primary care physician prescribed muscle relaxers which had no effect. My chiropractor scheduled an MRI on the 14th and we got the results on the 17th.

The MRI showed that I had a mass in my spine that was pressing on the fluid that protects and nourishes the spinal cord. My neck was screwed up more than anyone expected and needed immediate attention. A referral to oncology at Hoag Hospital got us into the ER on the 19th.

There was just one problem: my goddaughter was getting married on the 19th. On a sandy beach, at the end of a rocky path. And I could barely walk.

I’ve been a part of her life since birth and not being able to share this important moment broke me completely. I spent most of the 18th sobbing and feeling shitty about the cards that life had dealt me.

The tests included a two hour full–body scan in a noisy and cramped MRI. Plenty of time to contemplate life and realize that the last time I had been at this hospital was when my goddaughter was born 36 years earlier: a day spent translating for two women who were about to be grandmothers for the first time and didn’t speak each other’s language. (Little known fact: I’m an Italian godfather.)

All the tests confirmed the spinal mass and provided a plan for treatment. I was given steroids to reduce inflammation and felt immediate relief: it was the first time I had been without neck pain in about eight months. Next, a cervical laminectomy would remove part of my spine and permanently relieve the pressure on the spinal cord that was the source of my pain. It would also allow the doctors to obtain a sample for pathology: to determine if the mass inside my spine was benign or malignant.

The operation was a success and I was home in time for Thanksgiving. I was so thankful for my wife, family, friends, and medical professionals that were helping me through this rough time. And for the end of a week with opioid constipation.

After the holidays, it was not a shock to learn that the mass was malignant. Everything we had seen suggested that the source was lymphatic. Additional tests, including a PET scan and a lumbar puncture (a.k.a. spinal tap), made it clear that I have a follicular lymphoma in both my blood stream and spinal fluid.

The good news is that this is not a particularly aggressive variant and has therapies that have been effective for decades. It’s going to be something that takes months to treat and will require some hospitalization. But the doctors and I are both optimistic about the outcome.

The surgery to relieve neck pain continues to heal: I still have a bit of muscle soreness but the persistent pain is completely gone. Another reason to be hopeful for recovery.

I still have the nerve damage that caused my initial paralysis. The hope is that as the spinal mass shrinks, my walking and numbness will improve. And the only way to make that happen is with both physical therapy and chemotherapy, both of which I started on Christmas week. Happy holidays!

Luckily, I didn’t have any major issues during the first infusion, but a week later I’m still feeling the effects: overall fatigue, a queasy stomach, and a weird taste in my mouth. Dietary restrictions like giving up red meat, fried foods, and processed sugars seemed important a week ago. Now, the medicinal marijuana my nephew got me for Christmas feels much more significant.

It’s clear there is a long road ahead of me, and while I may have less spine, I am not spineless. The irrational dedication I mentioned earlier is now focused on getting myself back to health.

My personal goal is to swim to a buoy in the Pacific Ocean. It’s going to take a lot of effort to make that happen and I know that stating your objectives is the best way to meet them. (One of the reasons for this blog post, in fact.)

My goddaughters heard about my aspirations and handmade an inspirational gift for Christmas: candles of the buoy itself and the kelp and Garibaldi underneath. I’m going to burn it all down.

I had originally wanted to end this essay on that positive note, but the year had other plans. The week after Christmas, Pico started showing signs of abdominal pain and inappetence. He had developed a mass on his liver and spleen, and given his age, the prognosis for recovery wasn’t good. I always knew that saying goodbye to my constant companion of the past 15 years was not going to be easy, but never imagined doing it with all this other shit going on in my life. Consider my ass well and truly kicked.

Even if I’m getting out of the year on emotional fumes, I lived to see another one. My little boy won’t be there to dance around excitedly as I get out of the water this summer, but he will always be a reminder that I never give up.