Updated June 16th, 2025: I’ve never been happier to be wrong about something as I was on the eve of WWDC25. History did repeat, but in a good way.

As with the iPhone SDK, Apple decided to open up its language models for all developers to use. This lets third party developers leverage all the features available on each platform: we are on equal footing.

Additionally, App Intents have become much more useful, thanks to their adoption in Spotlight. The use cases for human–oriented activities are much more concrete.

While I still have concerns about the business aspects of being a developer in today’s ecosystem, the technical situation is exactly where it needs to be. Well done, Apple!

I’ve been developing on Apple products for a long time: typing PEEK and POKE code from magazines into an Apple ][, figuring out how QuickDraw worked using the Inside Macintosh pre-prints, having my mind blown by Mac OS X and every new thing prefixed with “NS”, and then jailbreaking the first iPhone so I could write an app that eventually won an Apple Design Award.

It’s been an exciting adventure. Until now.

The engineering behind Apple products continues to be amazing: Swift and SwiftUI have made it easier than ever to create products. The App Store continues to be the easiest and most vibrant marketplace to sell those products (in spite of the company’s attempt to screw that up.) Fricken’ amazing hardware, too.

So what’s wrong?

The problems we’re solving and the apps we’re writing haven’t changed in years. After almost two decades of iOS, everything is iterative. And while maturity is a good thing, it’s not the thing that gets developers excited.

We’re at the point where a big change is putting a new coat of paint on our creations. Sure, it looks nice, and customers will love it. But it’s a lot of work and none of it sparks our imaginations.

But what is exciting these days?

Large Language Models: a huge body of statistical data that can be leveraged to solve problems that have heretofore been intractable. It’s the most exciting technology in decades because it lets our imaginations run wild and create new things.

And that’s a problem for developers in Apple’s ecosystem. Because while the company has done a significant amount of research with these models, and includes one on every iPhone, iPad, and Mac, the core capabilities of the mechanism are out of reach.

It’s like if Apple’s products didn’t provide direct access to the camera. There would be no Instagram, no Zoom, no Halide, just the Camera app. Developers don’t get a shutter button: they can only access photos that have already been taken. Apple knows what’s best for customers, of course.

Developers have been in this situation before: at the introduction of the iPhone. We all saw a wildly innovative piece of hardware that immediately gave thousands of developers a revolutionary idea for a piece of software.

Maybe it was emulating a glass of beer, turning the device into a musical instrument, a game that could only be played by touch, or a way to connect millions of people using photos and filters.

Then Apple told us we couldn’t write native apps and had to make web pages instead. There was no way for developers to do the same things Apple was doing. This was, indeed, a shit sandwich.

Eventually, the company came to its senses and opened up the platform, dropped the ridiculous non-disclosure agreements, and allowed developers to do what they wanted. That led to a period of innovation like I’ve never seen: developers had something revolutionary and magic happened.

Now history is repeating itself. We have a new shit sandwich that’s called Apple Intelligence.

Instead of building our own ideas on top of an LLM, we’re supposed to provide the internal details of our apps to Apple so they can do it on our behalf.

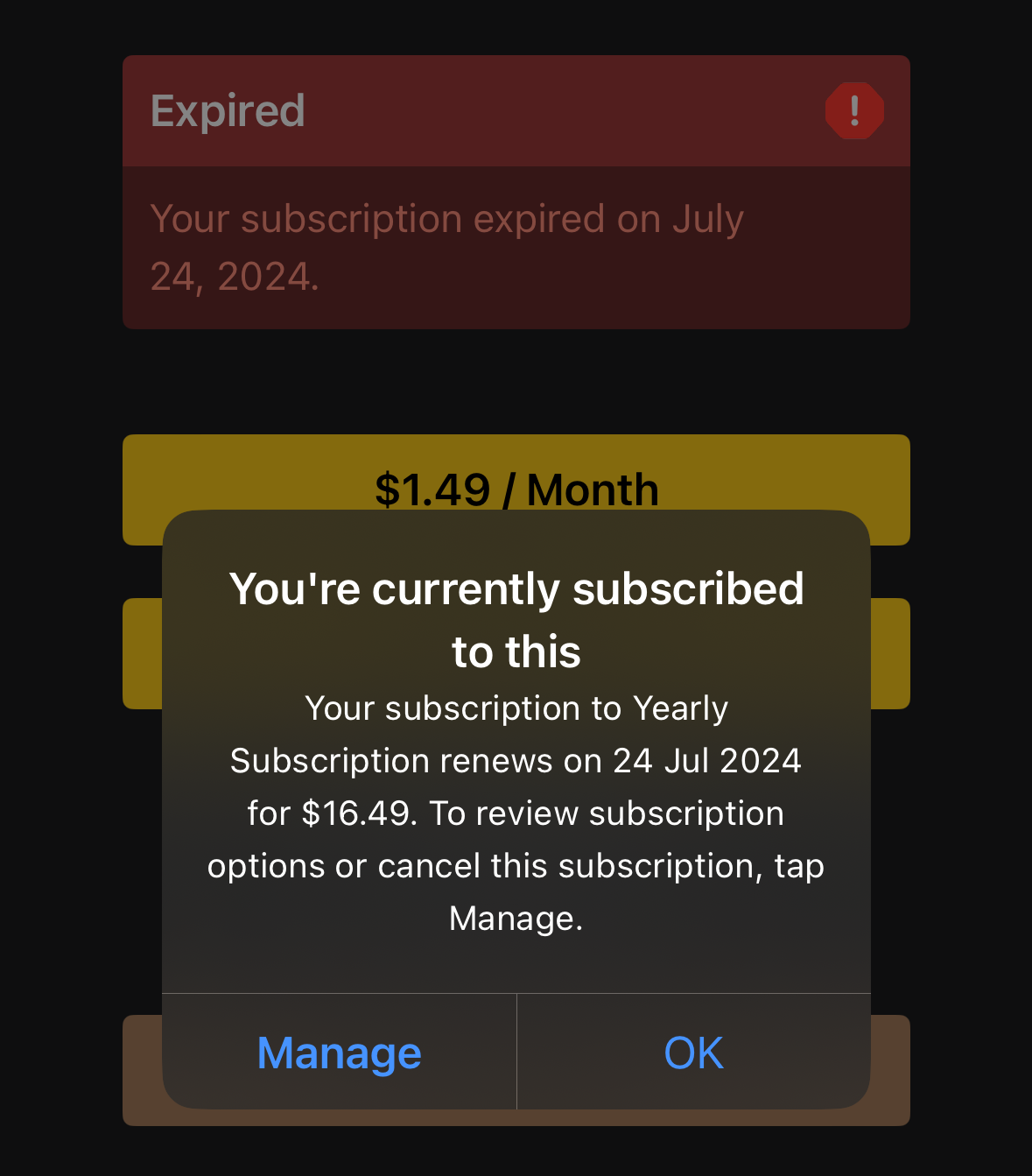

Providing those details is a lot of busy work for developers and not nearly as much fun as the coat of new paint: at least with visuals you can see and feel the results of your efforts. And from a business point-of-view, managing their internal details is why customers pay us. If Apple starts doing that on our behalf, what perceived value do we provide?

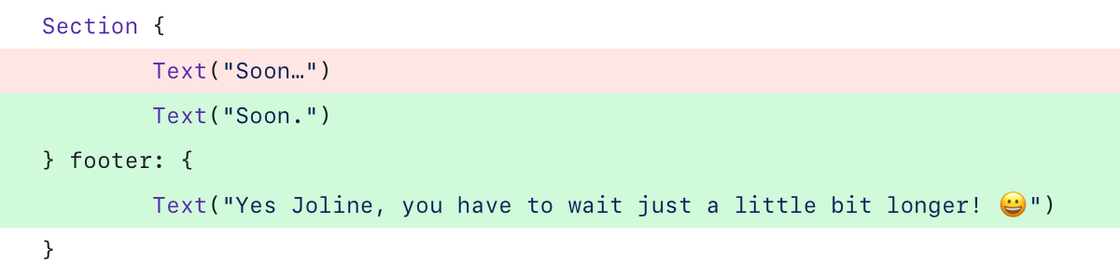

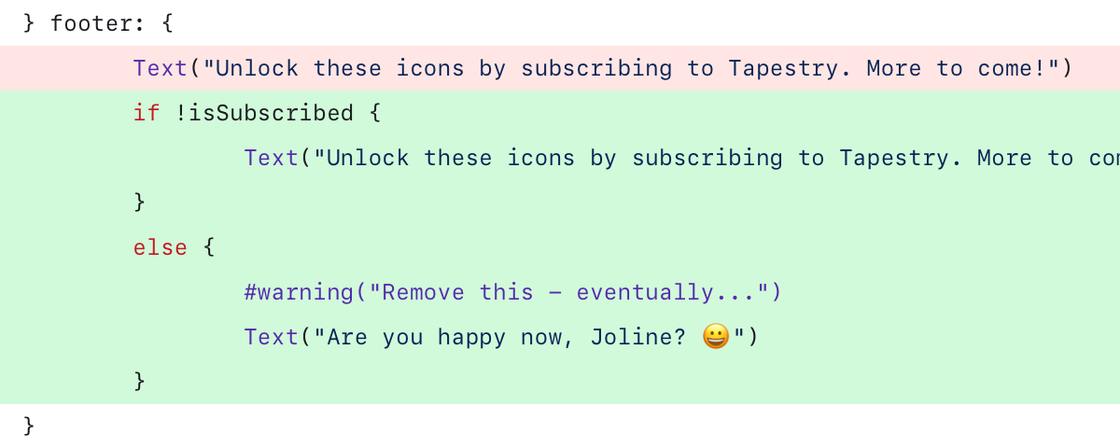

The internal details, called App Intents, are abstract and not something where you can immediately see the results of your efforts. It’s a “trust us Siri will be great at this” situation. Given the company’s track record in this area, there are few developers who think this will be successful. Worse, the improvements will be tied to lengthy release cycles: other companies drop language models with the frequency of new Emoji, not WWDC keynotes.

(I would not be surprised to learn that this whole situation is based on a fever dream of charging monthly service fees to use Siri and Apple Intelligence. These folks are seriously underestimating the reputational damage that Siri has incurred in the past decade.)

Some developers are working around this problem by providing their own models. This is unsatisfactory because it’s a waste of device resources: the downloads duplicate a tremendous amount of memory and storage. In many cases products are relying on cloud-based LLMs and losing all the privacy and security benefits of on-device processing.

All of this feels like Safari and mobile web apps in 2008: valiant attempts that everyone knows are wrong. Doing the best you can with a shit sandwich.

There are so many transformative ideas forming in developers’ minds right now that will never see the light of day. In our case, Tapestry has megabytes of textual information that describes a person’s interests and social connections. There’s no way for us to explore mining that data in a way that benefits the customer and respects their privacy.

(The developers who are making the greatest strides in this area are all doing it on the Mac. Ideas like Sky can thrive in a more open environment. Those of us in the jailbreak scene all saw how iOS borrowed heavily from its desktop sibling. Time will tell if that can happen again, but I suspect it will not given the locked down nature of mobile.)

So where does this lack of developer creativity lead?

It feels like developers are now part of the supply chain and being optimized accordingly. We are expected to refine and improve Apple’s ideas year-over-year. Our own needs and desires aren’t even secondary (where customers sit) or tertiary (our normal place in the hierarchy). We are just expected to deliver the products when Apple needs them.

I fear that this will lead to history repeating itself again, in a much more drastic way.

I remember how Microsoft’s response to the mobile revolution was to protect their existing desktop products. That looks a lot like Apple with its iOS franchise now. Instead of setting developers free, letting us experiment, and reaping the benefits, accountants and lawyers are fighting to keep us in line. We are all tired of the bullshit and many will happily move onto something better when it comes along.

Apple has been the lucky recipient of developer attention for a long time and they act like it will last forever.

It won’t.