I usually keep things fairly clean on this site. I have a simple metric: would I be embarrassed if my Mom read this post? As you’ve probably guessed from the title, this post is going to be different.

So, Mom, it’s time to stop reading. I’m pissed off and you know how I get when that happens.

In case you’re wondering what I’m talking about, look at this shit. A network process using 100% of the CPU, WiFi disconnecting at random times, and names, names (1), names (2), names (4). All caused by a crappy piece of software called discoveryd.

I started reporting these issues early in the Yosemite beta release and provided tons of documentation to Apple engineering. It was frustrating to have a Mac that lost its network connection every few days because the network interfaces were disabled while waking from sleep (and there was no way to disable this new “feature”.)

Regardless of the many issues people were reporting with discoveryd, Apple went ahead and released it anyway. As a result, this piece of software is responsible for a large portion of the thousand cuts. Personally, I’ve wasted many hours just trying to keep my devices talking to each other. Macs that used to go months between restarts were being rebooted weekly. The situation is so bad that I actually feel good when I can just kill discoveryd and toggle the network interface to get back to work.

Only good thing that’s come of this whole situation is that we now have more empathy for the bullshit that folks using Windows have suffered with for years. It’s too bad that Apple only uses place names from California, because OS X Redmond would be a nice homage.

It’s no secret in the tech community that discoveryd is the root cause of so many problems. There are even crazy workarounds. With so many issues, you’d expect some information from Apple explaining ways to mitigate the problems.

The only explanation I can come up with for this astounding lack of information is that there’s some mid-level product manager at Apple who’s covering their ass. I hope this person who’s responsible for withholding advice feels good about themselves, because the rest of us hate them with the burning passion of a thousand suns. Being stingy with knowledge in an engineering organization is a fucking stupid career move.

To give you an idea of how helpful a tiny piece of information is towards people’s productivity, let me give you a simple example that’s already saved me hours of frustration.

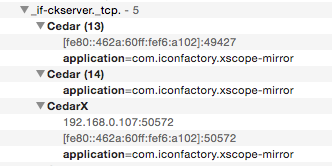

For months, I’ve seen bullshit like this in Bonjour:

That shows the xScope service on the Mac that provides data for the Mirror on iOS. In that screenshot, the service is being shown as available on three devices: one with just an IPV6 address, one with no IP addresses, and one with a duplicate IPv6 address and a valid IPv4 address. The name “CedarX” was the only way I could find to prevent names from incrementing (and breaking things that use the host name of that device.)

The “funny” thing is that this Mac is running the latest version of 10.10 with fixes for “WiFi issues”. And after tweeting about it in frustration, I got this response:

@chockenberry do you have airport extreme and Apple TVs on your network? Turn all Apple TVs off, reboot the airport. Power up the Apple TV.

— Hendrik ☠ (@Asmod4n) March 31, 2015

I followed Hendrik’s advice and guess what? No more network issues.

Bonjour keeps a cache that’s shared amongst devices on the network. This is so that if the device is asleep, another one that’s awake can provide the necessary information. I suspect that a device running an older version of discoveryd poisoned this cache. For some reason, the invalid cache information couldn’t be corrected by a newer version of the software which screwed things up in the first place.

But this is all just conjecture because Apple hasn’t written that fucking tech note.

This situation also shows another important aspect of the discoveryd clusterfuck: this code is all over the place. It’s in use by iOS, OS X and presumably whatever is running on the Apple Watch. As such, any one of those devices can poison Bonjour for everything else on your network.

This workaround is fairly simple if you’re on a home network where you have direct physical access to the all the devices. But as we all know, wireless networking is essential in places like an office, an airport or a coffee shop. Good luck rebooting everything in that kind of environment. And what happens when someone running an older version of OS X connects to that network and poisons it? Time to reboot!

You also can’t rely on software updates to fix everything: I have both an Airport Express and Apple TV that are no longer receiving fixes. Having to buy new hardware because of crappy software adds insult to injury.

Ironically, these issues are most likely to affect Apple’s best customers. The more devices you have, and the longer you have them, the more likely you are to get an unstable network. The only advice I can offer is to restart your entire network.

C:\ONGRTLNS.OSX